- Home

- Agop J. Hacikyan

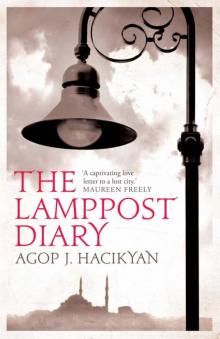

The Lamppost Diary

The Lamppost Diary Read online

Agop J. Hacikyan

THE LAMPPOST DIARY

TELEGRAM

Portions of The Lamppost Diary are set amidst political and historical events but the characters and their lives are fictional. The historical events, developments and episodes are based on personal eyewitness experiences as well as on books, articles, electronic reports and verbal accounts.

Except for place names, Turkish, Greek and Armenian words are spelled somewhat phonetically to reflect the original pronunciations.

First published in 2009 by Telegram

This eBook edition published 2012

© Agop J. Hacikyan 2009

eISBN: 978-1-84659-117-4

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

A full CIP record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

TELEGRAM

26 Westbourne Grove, London W2 5RH

www.telegrambooks.com

To Brigitte

for this book and for the others

that have been written through

the years of this precious journey

My loved one,

we have become mature

and it seems to me

that this adventure

that we have lived through

has lasted a thousand years.

But still, we are here

bare feet, hand in hand

running in the sun

children with amazed eyes.

Nazιm Hikmet, ‘Poems for Piraye’

Prologue

A chilly, colourless Sunday in November. The empty pews of St Vartan’s Church would soon be occupied. The chandeliers were dimmed. The air was cold and damp. Like a sleepwalker, Tomas tottered his way to the narthex and stopped in front of the picture of the Virgin Mary. He poured a generous drop of oil from the long-spouted copper ewer into the glass bowl on the table before the picture. The oil fed the flame of the tiny wick, igniting Tomas’s soul. He lit the candles he was holding – one for his mother, a second for his father and a third for his sister. He held them carefully, keeping them from touching one another. Then, raising himself onto his toes, he reached up to the high votive-candle tray and placed them side by side. He crossed himself three times and went back to sit next to his grandmother, who was in one of the pews reserved for women along one side of the church. His cheeks were slightly flushed. Grandmother Theresa checked her grandson’s hands and smiled, for they were clean. She asked the good Lord to bless her grandson so that he might be good, studious and obedient.

All through the service Tomas watched the three candles melt away. Before they burned out, he raked the sand, spread it over the candles and smothered them completely. Garabed, the old sexton, was standing at the foot of the stairs to the gallery, taking angry note of the boy’s conduct. Tomas took the remaining warm wax, moulded it into the figure of a child and buried it exactly where he had placed the third candle.

The deacon swung the thurible, smoke from the burning incense blending with the moist air. And the Mass followed.

Part One

1

Nişantaşι, a cosmopolitan neighbourhood in Istanbul.

A March morning with a low, dark sky, not yet dissolved into rain.

Tomas was running full speed. He was late for school. He stopped when he reached the rusty lamppost at the end of the street. He dropped his school bag onto the pavement, touched the metal pillar with his left hand, circled it three times, picked up the mud-smudged school bag once again and galloped off faster than before.

Tomas was convinced that touching the lamppost and turning around it three times every morning on his way to school would bring him luck, along with an enchanting, radiant day ... even the trees would yield fruit for him to eat during break.

The green rusty lamppost was so high it reached past the moon. It stood next to a huge Mobile Oil billboard: Pegasus, the winged horse, sprung from Medusa’s body. And, exactly there, the cobblestone street emptied into an exuberantly noisy, bustling road choked with taxis, handcarts, bicycles, trams, carriages, errand boys, vendors, men, women and children. Taxis honked incessantly, an orgy of blaring horns – the clamour of unbounded energy that upholds every big city. A horse-drawn carriage blocked the slow-moving traffic; the sound of screeching brakes filled the air. People shouted curses stale from overuse; peddlers put their merchandise down on the pavement so they could watch. A policeman, useless as a stiffened paintbrush, stood nearby tooting his whistle. There was no reason not to remain calm. Such turmoil was a daily occurrence and always brief. Suddenly, the mulish horse lurched forward, and with it the traffic.

Tomas ran faster than his shadow. He was racing against a pair of trams going to Harbiye, the military school – a red car for first-class passengers connected to a green one for second-class and classless commuters. He checked his watch; he was very late. He dashed by Nargil’s pharmacy, Togo’s bakery, Yordan’s dairy, then the jiğerji. If he hadn’t been in a hurry, he would have stopped to inspect the lamb and calf livers, lungs, kidneys, sweetbreads and hearts lying next to each other in the butcher’s window. Once a week his mother bought calf liver for the family, and pieces of lung for Jambaz their cat.

The nine-year-old boy had been named after his paternal grandfather. He knew his grandfather only from the massive sepia portrait hanging in the living room: a thick handlebar moustache and a pair of melancholy black eyes, as if permanently conscious of his tragic destiny. There was nothing distinctive about the younger Tomas’s appearance – except for the birthmark on his left eye. People who saw him for the first time thought he’d been in a fight. He was also left-handed, and was frequently punished for it. At school, when Father Matos wasn’t talking about sin, masturbation or confession he digressed: God created the right hand for people to write with ... to eat with ... to shake hands with ... and, above all, to cross themselves with (completely forgetting its usefulness for wanking). As for the left hand, it should be used only for mundane, unspecified activities. Tomas was forever being reminded of the horrendous afflictions meted out in hell to left-handed people.

Matchstick was Tomas’s nickname. Despite his mother’s extraordinary efforts to fatten him – stuffing him with cod liver oil, olive oil, castor oil, motor oil and tahini, bloating him with rice, bulgur and wheat, sweetening him with pekmez, halva, baklava and kourabiya, cleansing him with herbs and flowers in case of tapeworms – Tomas kept growing at an anomalous speed, but alas, always remaining skinnier than the shadow of a piece of macaroni.

Their neighbour’s son was the inspiration for Tomas’s morning routine. The short, chubby, curly-headed, likeable nine-year-old lived in the same building. Every morning, before leaving his family’s apartment, Seth touched the mezuzah screwed to their doorpost. Tomas had been told that there was a prayer in it. It signified the sanctity and blessing of a Jewish home. Before he knew what a mezuzah was, Tomas thought his neighbours had nailed a toy submarine to their doorway.

Why had his father not put an Armenian mezuzah in their doorway, with a short Armenian prayer in it – so one could touch it and be blessed, or ignore it and be damned?

Tomas would have preferred to put his hand on such a mezuzah instead of a lamppost, around which he then had to turn three times. Father Matos had explained to the class that three was a sacred number – it represented the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit. ‘Three is life,’ he would say. Tomas couldn’t see any relationship between life and the number three. He did know, however, about The Three Musketeers. He knew all about Athos, Porthos and Aramis, those daring children in adult bodies. He had seen the film three times.

Tomas was still in the race. Another traffic jam, another stand-down. Everything was being pulled forward inch by inch. Then the tram screeched. The vatman tapped on a conical rubber button with his right foot and discharged ear-piercing rings to make the pedestrians move aside, then the car picked up speed, skipped a stop – no passengers to get off or on – and shot ahead as if to catch up with Tomas, who was by then gasping, ready to collapse.

Swirls of grey dust rose from the pavement. The weather resembled Tomas’s state of mind. He stopped momentarily. Was it because of him that the sky had clouded over so threateningly?

*

The last two weeks of summer. Colours still persisted, refusing to fade away. The family was at their seaside summerhouse in Tarabya along the Bosporus when Tomas’s sister, Emma, tumbled down the stairs from the second to the first floor. She was rushed to hospital. The eerie siren of the white ambulance with the red crescent on both sides still reverberated in Tomas’s ears.

Their Greek landlady insisted over and over that his sister had skidded on the ‘slippery beams of brightness’.

Her words gave Tomas the creeps. What was she on about? ‘The slippery beams of brightness!’ From that day on he despised everything bright and shiny. Their three-month-long summer holiday came to an abrupt end and they returned to the city. Tomas missed going to Ibrahim’s travelling circus to watch Asaf walk the slack tightrope that was ready to break at any minute, he missed Asaf’s colouring-book face. There were still two weeks before the schools reopened.

Tomas stayed with Grandma Theresa, across from St Vartan’s Armenian Church, where Tomas was baptized. Grandma Theresa lived with her son Zenon, a perennial bachelor, and her daughter Arminé, who had lost her husband before her son Azad was born.

Tomas hated Grandma Theresa’s five-room apartment. It spelled boredom and gloom to him. The furniture was ugly. The sofa, with wooden arms like miniature ironing boards, its brown printed velvet cover barely held in place by nasty gold upholstery nails, made him feel more despondent than the enamelled grey wood stove with its black pipe that crept like an oversized boa over the ceilings of the apartment. The Crosley radio was the only acceptable piece of furniture, lavished with care over the years. When not in use it was covered with a made-to-measure piece of embroidered linen. Only his Uncle Zenon had the right to touch the radio. He turned it on mostly for the news. It was as if he were listening out for hints of bygone events in the newscaster’s voice. For music, he preferred to play a version of ‘Paris je t’aime, je t’aime, je t’aime, comme une maîtresse ...’ on his mandolin, which was kept in its case under the bed. The bedrooms and especially the kitchen, confused Tomas terribly: bottles, salt cellars and pepper grinders, plates, glasses, forks, knives, corkscrews, umbrellas, chairs, lamps, commodes, knick-knacks, shoes and many other items were hidden under small paper bags or covered with worn-out sheets and bed covers. Tomas had the impression that Grandma was ready to move to an unknown destination at any moment. It was, perhaps, a syndrome, or a curious virus caught during their deportation days.

From the living room window he could see a black hearse parked in front of the church – always the same black box-shaped carriage with silver-coloured wooden flowers affixed to its roof, a coffin displayed on an open platform in the back. It was a platform of witches, magnetically drawing onlookers to a slippery world beyond. When there was no hearse around, Tomas looked out on the drab scenery – rows of uniform three- or four-storey apartment buildings, many of them run down, and a tinsmith’s shop, the door and windows of which had been boarded up years ago. At night the streetlights cast their glow over the pavement and the cobblestones. Everything looked like a picture in which life had suddenly stopped.

His father kept repeating, ‘Your sister will be back soon.’

The days never seemed to end.

His father said, ‘Your mama is staying with Emma at the hospital. Too bad hospitals don’t allow children to visit patients!’

The clocks didn’t move on; the minutes were on strike.

Tomas was lonely, like a forgotten heirloom in the attic. He wanted to go out, to walk purposefully about the neighbourhood, but he wasn’t allowed to leave the apartment alone. He dreamed of the days when the family was together. Days once so near were now unattainably far behind. The people around him broadened their kind smiles. His family seemed to have lost control; every little word turned into a major squabble. And yet at other times they wrapped themselves in silent melancholy. Tomas spent much of his time playing with old imperial Russian banknotes, aborted investments, which were kept in abundance in chests or suitcases in many Armenian homes; looking at old family albums, deciphering newspaper headlines; or observing the ants and cockroaches as they worked diligently under a large stack of wooden and cardboard boxes on the balcony. Sometimes, seized by a sudden urge, he would flush them down with water through the narrow drainpipe to the interior courtyard below. This would lift him out of his inner emptiness, at least temporarily. In no more than two or three days another battalion of bugs would reclaim the area and continue working beneath a thick layer of black city soot. Occasionally songbirds would alight together on the window ledges. Tomas wished they would stay forever, but they never stayed for long. He would have liked to go out to the courtyard and talk to the dandelions, but he wasn’t allowed. Sometimes he wished it would snow – ripe flakes that made him dream of Emma vanishing over slippery luminous beams of light – but it never snowed. Other times he would simply shut his eyes and disappear into the world behind his eyelids.

One evening, as they were having supper at his grandmother’s, Tomas noticed that the light in his father’s eyes had disappeared.

‘What’s the matter, Papa?’

Papa leaned back weakly in his chair. ‘Emma’s been taken to Switzerland. Mama’s gone with her. They have good doctors in Geneva.’

His words slid like cold knives into Tomas’s tender flesh. His big bright eyes searched Aunt Arminé’s face for help. He didn’t know where Geneva was, but it sounded very remote. He begged quietly for his aunt to say something, but she remained mute.

*

Tomas was at last in front of the school building.

He walked through the large cement jaws of the gateway, arriving at the students’ entrance. He pushed the wooden door open with his foot, took off his hat, tiptoed along the marble corridor and climbed up to his classroom on the first floor. He hung his coat in the cloakroom and, after a moment’s hesitation, decided to go in. He opened the door just wide enough to squeeze through. The lights were on because the cloudy day had darkened the room. The floor creaked under the weight of inscrutable silence. The teacher sat behind his desk on a raised platform, staring sullenly at Tomas as he walked to his desk and sat down next to Aram Avakian. The classroom was cold. The teacher always kept the windows wide open, even in the harshest of winters, to keep the class from sleeping. A pupil was busy doing multiplication exercises on the blackboard.

Entering the arithmetic class late was risky, almost fatal. The tall, balding, skeletal teacher with awkward limbs and steel-rimmed spectacles would have been better suited to an anatomy lesson than to the teaching of addition and subtraction. He was likely to gracefully stretch himself like rubber, twice as long and twice as thin as his habitual stature, coil himself around Tomas’s neck, chest and waist, and squeeze the life out of him. His increasingly fierce comportment, which was well known to everybody, both within and outside the school, had rightfully earned him a

reputation as a sadistic maniac. Baron Garig’s notoriety, in spite of his passable pedagogical qualities, had clung to him for a very long time. And what was so remarkable was that no one had ever thought of dismissing this brutal calculating automaton. Tomas was puzzled. Why didn’t Garig ask him why he was late? Instead, he turned to the pupil at the blackboard and told him to continue.

Aram and Tomas shared a desk. Aram was repeating the third grade. He was more interested in playing, eating and stealing fruit from the baskets in front of fruit shops than studying. This freckled, ruddy-faced boy was Tomas’s partner in crime. They saved their allowances to go to cowboy films. And when they had no money they enjoyed hanging around the entrance of neighbourhood movie houses, looking at the stills and posters on the walls until the ticket girl came out of her glass booth and chased them away.

‘You’re late.’

Tomas shrugged.

Aram giggled. ‘Look at this.’ He pointed with his ink-stained finger at the comic he held in his lap: a picture of a man and a woman kissing. His black eyes twinkled with impish joy.

Tomas grinned. ‘Put it away; we’ll get in trouble.’

‘Look at them,’ Aram insisted.

The teacher placed an index finger against his lips. Tomas was even more puzzled. Ordinarily he would confiscate the magazine and send them to the principal’s office or, with a vicious smile, ask them to step forward and order them, Tomas first, to hold out a hand, then bring his long ruler down on it with a loud whack: one, two, three, four ... the ruler would come down again with four quick smacks on the other hand. Then, with equal vigour and passion, his face and jowls purple with rage, he would tell Aram to hold out his hand. Tomas, squeezing his hands under his armpits and fighting back tears, would watch Aram go through the same punitive therapy. Then they would be sent to the principal’s office. The thought of going there brought with it the solemn smell of leather and musty rug.

The Lamppost Diary

The Lamppost Diary